Psychology

This piece was originally featured on Research Matters.

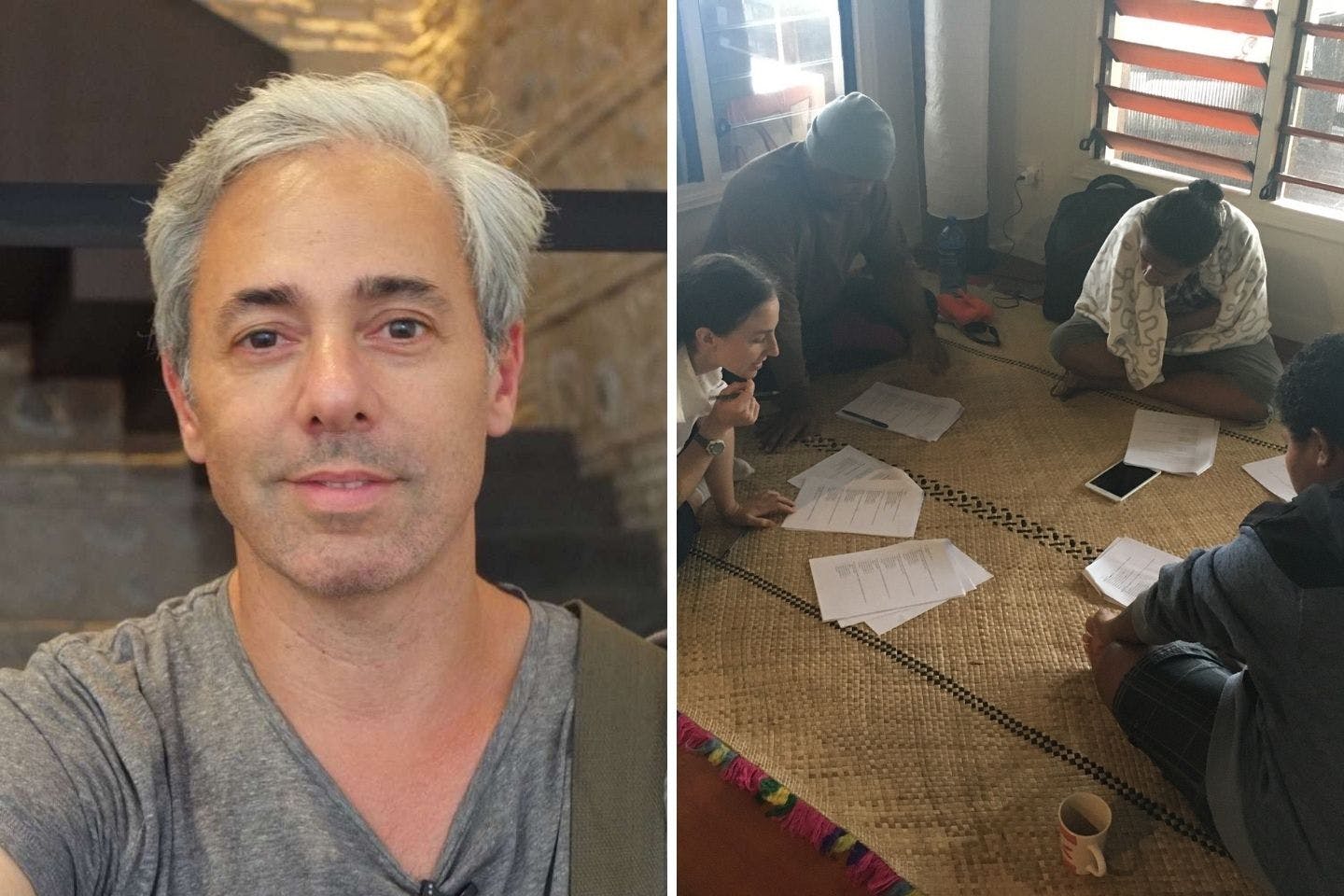

The National Science Foundation recently awarded Jeremy Ginges, Associate Professor of Psychology, a major grant to support a multiyear research project entitled “Religion and Human Conflict.”

The award, totaling $646,716, will support Ginges and the members of his Social and Political Psychology Lab — including New School for Social Research Psychology graduate students Anne Lehner and Starlett Hartley, and postdoctoral fellow Mikey Pasek — as they develop, according to their abstract, a “theoretical framework that will allow us to understand, predict and model how religious belief influences intergroup relations, sometimes encouraging cooperation and tolerance, and at other times promoting conflict.” A supplemental award of $47,700 will allow Ginges to involve six undergraduate students from underrepresented groups from Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts in the research project as well.

Throughout his career, Ginges has focused his research on two main questions: How do humans decide whether to cooperate across cultural boundaries, and why do people sacrifice everything (their own lives, the lives of loved ones) for an abstract cause like a nation or a god? He and his lab members have investigated these questions in places around the world that oscillate between “extreme conflict and surprising cooperation,” such as Israel-Palestine, Lebanon, Fiji, and Indonesia.

“The mainstream view was that beliefs in moralizing gods [gods that police behavior], and different divergent beliefs in gods….spread because they help groups become tightly knit cooperative entities that could outcompete other groups. It’s another way of saying they cause intergroup conflict,” explains Ginges. “We’ve been doing research showing that that’s actually not the case.”

In a recent article led by Julia Smith, an NSSR graduate and current doctoral candidate at the University of Michigan, Ginges and his co-investigators show that, contrary to those mainstream views, belief in moralizing gods actually discourages dehumanization of other ethnoreligious groups. His lab is currently preparing a paper on an experiment in which participants were given a set amount of money and encouraged to share it with strangers. Participants initially gave more money to members of their religious group, but when prompted to think about their god, they ended up giving more money overall, regardless of who they were interacting with.

The NSF grant will help Ginges and his lab members better understand exactly when and how belief in moralizing gods makes intergroup relationships better, and when and why it sometimes makes them worse. In the case of the money-giving experiment, if a norm is to share money, thinking about god will enhance that generosity. However, if a norm is to fight a different ethnoreligious group, then thinking about god might instead increase that aggression.

In addition to better understanding how religious beliefs may have shaped, and continue to shape, cooperation between people living in diverse, complex societies, Ginges hopes that his research may inform public policy on a range of issues.

“There are implications for this research in how we understand issues around multiculturalism, particularly religious diversity and immigration,” he explains. “And also, understanding more deeply when religious belief can be used, or is used, to promote prosociality can help organizations aimed at encouraging cooperation.”

Given improving pandemic conditions, Ginges is hopeful that he and his lab members can begin running filed experiments in this multiyear project in Fall 2021. Research and fieldwork will take place with participants in the U.S. as well as Israel-Palestine and Fiji.